The Great Gusto of Jimmy Binns

BY PHILLYMAG |

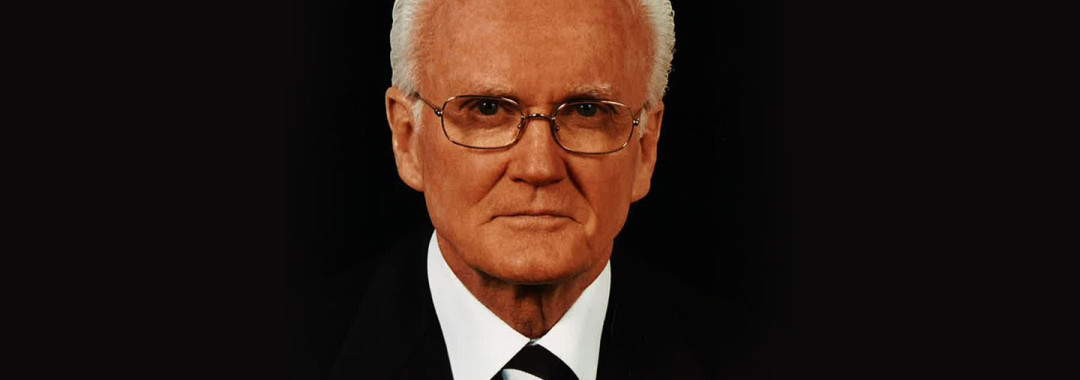

IT’S HARD TO KNOW which Jimmy Binns story to start with, because Jimmy Binns is nothing if not a cultivator of vivid stories. Some rise or fall on his profanity, and some on his comic timing, and honestly, some Jimmy Binns stories are fun simply because they involve somebody getting his ass kicked by a 66-year-old man, which Jimmy Binns is. But at root, these stories all share the same punch line: the contrast between the man Jimmy Binns is — i.e., the pinstripe-wearing, wealthy old Philadelphia lawyer who is chummy with U.S. senators and has paintings of fox hunts on his walls and is a fixture in international boxing circles and says he was charging $500 an hour in the 1980s for his legal services and who today charges “a lot more than that, buddy” — and the man Jimmy Binns becomes in his stories, which is an ass-kicking tough guy tougher than anyone from Rocky V, in which he “portrayed himself,” like it says on his business card, “as Rocky Balboa’s lawyer.” Rocky’s lawyer: a Daily Double of iconic Philadelphia types. Not just the Philadelphia-lawyer type, and not just the Rocky type, but Rocky’s lawyer. In fact, if you were to sculpt a statue of the Ultimate Iconic Philadelphia Male, a man who wasn’t just a tough guy or a Main Liner but was both at the same time, a man who could curse like a drunk Eagles fan and throw left hooks like he trained with Frazier and also kick back with the power elite at the Racquet Club at the end of the day, you couldn’t do better than to sculpt Jimmy Binns. And he’d be more than happy to pose for you.

Since I’m a writer, Binns didn’t pose. He told me stories, some from years ago and some he created for my benefit on the fly, and in all of these stories Binns came across as so Philly he couldn’t possibly be for real. For instance, here’s Jimmy Binns, the old man, leaning back in his chair at the Italian bistro Radicchio, next to a framed caricature of himself on the wall, telling me about his 1992 divorce (“I’m single now”) and then jabbing his thumb at a girl in a pink top at the next table and adding, “But maybe not for long.” Binns’s voice isn’t self-consciously leering or ironic or anything; the girl’s 28, tops, and Binns is smiling through his perfect white teeth. He’s trying to make it sound credible — at least as credible as the left hook he says he delivered, a few years ago, to a sauced Two Streeter who was (Binns says) making threatening gestures up on Market Street. After the Two Streeter dropped to the pavement, the story goes, Binns told the guy’s friends, “When he wakes up, tell him an old man did it.”

Another story: Here’s Binns giving me a tour of his immaculate four-story house in South Philly. He’s showing me his certificate of admittance to the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court. And the U.S. flag given to him by his friend Congressman Bob Brady. And his congratulatory letter from ex-governor Bob Casey re: the dedication of the James J. Binns Fitness Center at La Salle University, where he served on the board. The place is like a museum of his own power and connectedness and Philadelphia-lawyerly fabulousness. And then Binns picks up the heavy coffee-table book of Tony Ward, the famous photographer who shot him for this very story, and, as I flip through the book’s arty female nudes, says: “Oh, you haven’t seen anything yet. There’s one picture there of a woman with a high heel up her asshole and her finger up hersnatch.”

And there it is again. His defining characteristic: the self-conscious high/low, street/elite straddling that gives him a special kind of power. Congressman Bob Brady says of Binns, “If I needed some kind of help on a charitable issue, I would call him,” because Binns is “a gem for the city” who is “accepted on every circle and every level.” Binns isn’t the attorney in the back room with Art Makadon and David Cohen, banging out deals. He’s the guy with the fattest and weirdest BlackBerry contact list: congresspeople, crooks, beautiful women who speak exotic languages, barbers, deejays, famous writers and lawyers and boxing promoters, rabbis, Don King. He’s the guy who can get a good chunk of those people to come together to, say, hand out free turkeys to the poor. He’s the guy described by federal appeals judge Edward Becker as “a very able lawyer” and also “quite … stylish.” He’s the guy who is referred to by his client Shamsud-din Ali, the reputed ex-Black Mafia figure-turned-imam whom Binns defended against racketeering charges in 2005, as “Rafiq Ali,” meaning “honored and trusted friend of Ali,” while across the aisle, Philadelphia PD Chief Inspector James Tiano can tell me, in all seriousness, that if Binns had a religion, he’d join, because “I’m a Binns-ey-ite.”

Where does a guy like that come from? The straight answer is that he comes from the part of the Northeast now known as Mayfair, and then Mount Airy. The truer, more abstract answer is the one given by Tom Welsh, former assistant squash pro at the Racquet Club. “Jimmy’s a character straight out of a pulp-fiction novel,” says Welsh. “He’s certainly a man among men. You would think he grew up in the ’hood somewhere, as opposed to his true background.”

Which may be the best Jimmy Binns story of all: the story of how Jimmy Binns made himself a pulp-fiction character and a man among men in a city that doesn’t look kindly upon self-invention; the story of how Jimmy Binns created Jimmy Binns.

AND, HONESTLY, he told me that story, too. It wasn’t some mystery I had to laboriously unearth. When I started hanging out with Binns back in August 2004, everything seemed to happen at once, in an overwhelming continuous Binnsian moment that engaged all the senses and the peripheral vision, so that for a while I walked around in Binns-space like those shoppers you see at Costco, the first-

timers, dazed at the profusion of high shelves, not sure where to look. Sometimes his clothes alone could do it, like the time he showed up for dinner wearing a sea-green checked shirt and a matching green blazer and a green leather belt, his skin pinkish, his Irish nose convex, his jutting pugnacious chin as jutty as ever, his perfectly white hair slicked back, the juxtaposition of white and green making him look like a giant breath mint. Sometimes it was the whole scene he created, the big picture. That month, Binns took me to a fight in Essington, at the Lagoon, whose ring was surrounded by palm fronds — and Binns just sat ringside in spats and a diamond-studded Rolex, silent as God, the apparent fulcrum of all these mad characters: some promoter who’d flown in from South Africa, and some loud, mustachioed guy Binns called “the biggest sausage man in South Jersey,” and Shamsud-din Ali in a dark suit, and Binns’s 27-year-old son James Jr., heavier than Dad but with the same hawk haircut and yen for self-promotion. (Jr., who owns two nightclubs in New York City, told me he plans to launch a line of sweatsuits that say BINNS, COMING SOON on the front.) Binns called me the next day and said, “So, do you feel any different now, after your first fight? You know, it’s kinda like losing your cherry.”

It was great material. It was like stumbling onto the set of a movie already in progress, and Binns was the star but also the director, exercising control over the lighting, soundtrack, ambience, setting, dialogue. Which, as I spent more time with him, started to seem a little odd — the degree of his control. Every story and image felt punched up with color and noise, prepped for celluloid. I once overheard him ask a waitress at the Palm to replace its wall caricature of Jimmy Binns with a different caricature, one that hangs on the wall of Radicchio, because the Palm caricature was “too realistic” — “It looks too much like me.” Binns likes the Radicchio caricature because it was drawn by his friend, artist LeRoy Neiman, and because Neiman portrays him dashingly, in a red tie and his trademark pinstriped suit, looking down his Toulouse-Lautrec nose with radiant pity. The caricature is reproduced on the front of his business card in glossy color. The back of the card is just as attentive to image as the front, reading, in part, “Criminal and Civil Trial lawyer … decisions over Muhammad Ali … Don King, Mike Tyson, and the E.E.O.C. … Former Pennsylvania Boxing Commissioner … Represents boxing promoters and casinos throughout the world … Portrayed himself opposite Sylvester Stallone, Talia Shire & Burt Young as Rocky Balboa’s lawyer in Rocky V.”

His narcissism — and that’s really the only word for a guy who puts an illustration of himself on his business card — was so over-the-top and unapologetic as to be kind of charming; and anyway, it wasn’t narcissism for narcissism’s sake. It was in the service of a great passion for a certain kind of story he grew up with as a kid, the source of which he showed me once, in his office in Blue Bell. From his bookshelf there, he plucked his red-covered, yellow-paged copy ofA Treasury of Damon Runyon. I knew exactly what it was, because he’d told me. TheTreasury was the blueprint of Jimmy Binns; it was the mold that made him.

To continue reading article click here to visit phillymag.com.